Sequins and Ginger

Abstract

This paper references two episodes, set in the Caribbean, from director Cheuk Kwan’s 15-episode documentary series entitled “Chinese Restaurants” – a work that takes the director on a journey to thirteen countries around the world as he explores the Chinese Diaspora through the icon of the Chinese Restaurant. Using Kwan’s visit to Soong’s Great Wall – a restaurant in Trinidad owned by Maurice Soong, a Hakka who migrated from China to Trinidad in 1948 – and Kwan’s trip to Cuba where he experiences a Chinatown tourist attraction through his visit to Havana’s Lung Kong Restaurant, I explore the “overseas Chinese” identity in the Caribbean component of the Chinese Diaspora. I argue that through the portal of the Chinese restaurant in certain islands of the Caribbean, the “overseas Chinese” identity can be seen as pivoting on participation in forms of masquerade or mas playing (public engagement with Trinidad’s carnival festival in one instance and participation in government-endorsed costumed stereotypes and exotification in the other instance) in order to enact Caribbean citizenship.

Introduction

The black experience,’ as a singular and unifying framework…became ‘hegemonic’ over other ethnic/racial identities.

– Stuart Hall, “New Ethnicities.”

Although Stuart Hall was speaking with respect to the context of Britain, his remark has resonance in the Caribbean region. Discourses of Caribbean identity, nation and society have thrown intense light upon a Caribbean experience suffused with African influences. Indeed, we cannot get away from a knowledge that the largest immigration of peoples into the Caribbean between the sixteenth and late nineteenth centuries, were African. We cannot evade the reality penned by O. Nigel Bolland who declares: “African cultural influences are pervasive in the Caribbean and they are widely shared by people who are not of African descent.” Furthermore, scholar Rex Nettleford observes: Caribbean islands such as Trinidad, Cuba, Guyana and Jamaica cannot “escape the fact of the African Presence in the national cultural ethos.” Yet, this paper is not an attempt at academic escapology. Rather, this paper proceeds with an understanding that “hegemony [whether historiographical or otherwise] is never permanent,” for the power that is inherent in certain members of a society having greater visibility, more robust representation and more muscular vocality, can shift.

This conference becomes part of a negotiation process for such shiftings. This paper, therefore, creates a space for the spotlight of scholarly inquiry to shift and shine upon other actors on the Caribbean stage. It is a paper, which takes up the subjective position and experiences of the “overseas Chinese” in the Caribbean. I reference primarily, two episodes – one set in Cuba and the other in Trinidad – from director and producer Cheuk Kwan’s 15-episode documentary series entitled “Chinese Restaurants” – a series that takes Kwan on a journey to thirteen countries around the world as he explores the Chinese Diaspora through the icon of the Chinese restaurant. I examine performance – specifically enactments of citizenship. Using May Joseph’s conceptual framework of citizenship as an embodied condition “acquired through public and psychic participation,” I argue that through the portal of the Chinese restaurant and beyond Chinese kitchen doors in certain islands of the Caribbean, the “overseas Chinese” identity can be seen as pivoting on public participation in forms of masquerade or mas playing in order to act out roles as Caribbean citizens.

From China to the Caribbean

The experiences of the “overseas Chinese” deserves attention, for the majority of the Chinese who migrated to the Americas in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries came from South China yet, according to Wang Gungwu not all Chinese, especially those from provinces “in north and west China which never produced such [overseas people]…care for…or even know who or what [the overseas Chinese] are.” While the English term “overseas Chinese” seemingly implies any Chinese people residing outside the People’s Republic of China, the issue of citizenship becomes a key factor in distinguishing very specific Chinese interpretations of Chinese who went overseas.

Walton Look Lai observes that the Chinese came to the Caribbean in two distinct historical periods, not including immigration since the 1980’s. Chinese people first came as indentured laborers in the 1850’s and 1860’s and a second wave of Chinese arrived as free migrants from the 1890’s to the 1940’s. This second wave is significant in two ways. First, this second influx of immigrants gives us a foothold in understanding early conceptions of the term “overseas Chinese,” for these immigrants constitute a Caribbean subset of “overseas Chinese” who were known as the Huaqiao. The Chinese term “Huaqiao” or “Hua-ch’iao” refers to a politically charged identity. Between 1893, when the overseas travel ban was lifted by China – allowing Chinese people to officially journey outside China – and the mid 1950’s, the Huaqiao were Chinese people who had political recognition and approved residence abroad. The Huaqiao were regarded as important political extensions of South China and they were rallied to enter China’s government politics and become vital forces in gestures of revolution and nationalism. Kathleen López writes: “the Chinese in Cuba and throughout the diaspora…had to imagine themselves as part of a Chinese nation before they could fully participate in the nationalist movement.” Today, the term “Huaqiao” now refers specifically to those Chinese who live abroad but retain Chinese citizenship, while the Chinese term “Huaren” describes Chinese living outside China who attain naturalized citizenship in the country in which they reside. It is clear here that the notion of the “overseas Chinese” is not an uncomplicated one and delimitation of the term is required for the scope of my current inquiry. This leads me to the second way in which Chinese immigration during the 1890’s to 1940’s is significant.

The second wave of Chinese immigration to the Caribbean is also important because as Look Lai documents: “most of the modern West Indian Chinese are descended from…this group.” The Chinese use the term “Huayi” to refer to “overseas Chinese” descendants who were born and have grown up outside China. In this paper the term “overseas Chinese” refers to the “Huayi.” I focus on Huayi subjectivity, that is, the playing out of being a native Caribbean Chinese citizen.

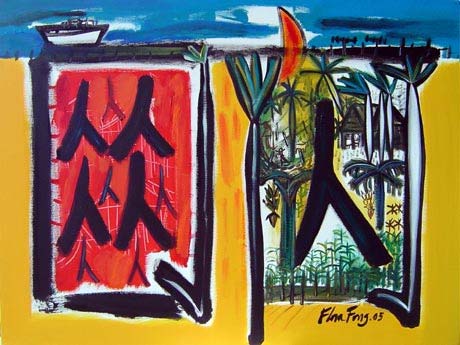

This matter of being Chinese in the Caribbean is given space in works by those like Flora Fong and Cheuk Kwan. In Cuban Chinese artist, Flora Fong’s 2005 painting entitled “De China al Caribe” or “From China to the Caribbean” (see figure 1), she uses the “rén,” a Chinese character meaning “person” (see figure 2). In doing so, she emphasizes the human, experiential dimension of migration and hints at the personal stories of being Chinese that can be told by Caribbean Chinese persons. So too, Hong Kong-born, Canada-based documentary director Cheuk Kwan engages with what it means to be “living Chinese” in the Caribbean. Kwan probes the Chinese restaurant – which is as much a part of the Caribbean as sun, sea and sand – to uncover personal stories of Chinese migration, culture, survival and identity. Kwan writes: “As a group we may be called the Chinese Diaspora but as individuals we all have our own identities. My restaurant stories…deal with the…highly personal nature of this identity…” Kwan points his camera at Cuba and Trinidad – the two Caribbean islands in which Chinese laborers were brought to work on sugar plantations while African slavery was still operative. It is to these islands that I now direct my own lens.

Fig. 1. Painting by Cuban artist Flora Fong, De China al Caribe [From China to the Caribbean]. 2005.

Fig. 2. The rén, a Chinese character meaning “person.”

Cuba

A small number of Chinese live in Cuba. One factor contributing to a decrease in the number of Cuban Chinese is the greater male to female ratio of Chinese migration to that island. Kathleen López observes that the Cuban Chinese community today comprises “the remaining native Chinese, and the children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of Chinese, most of whom are descendants of a Chinese man and Cuban woman…it is these mixed descendants who form contemporary Chinese Cuba.” Director Cheuk Kwan comes to Cuba and is amazed to find so few Chinese there. Kwan meets Alejandro Chiu, the owner of Lung Kong Restaurant in barrio chino – an area of Havana Cuba that was “one of the best-known Chinatowns in the Americas.” Kwan is taken into the Lung Kong Restaurant kitchen where he sees “bare shelves and almost empty refrigerators. [There] the most popular item on the menu seems to be pizza while Chinese noodles are made with Italian spaghetti.” Yet, beyond this stark kitchen, which serves up Chinese food unlike any Kwan has eaten, is the remaking of the Orient and a parading of native Cuban Chinese in the colorful costumery of what Edward Said has called Orientalism – all in an effort to satisfy the Caribbean tourist’s palate for the exotic.

According to Said: Orientalism as a discourse manages and produces the Orient politically, sociologically, ideologically and imaginatively. Said pinpoints the phenomenon of Orientalism as a body of ideas about the Orient that has been constructed by the West; those ideas about the Orient that have little or no ties with a “real” Orient. Barrio chino is part of these unreal ideas. The Chinatown is now a Chinese fantasy constructed by the Cuban government. López writes in her piece on the Chinese in Cuban history that “with the end of subsidies from the former Soviet Union…the Cuban government formed the Grupo Promotor del Barrio Chino de la Habana (Havana Chinatown Promotion Group) to ‘recover’ Chinese culture, customs and traditions for the Cuban community and attract hard currency revenues…The priority is to transform the historic barrio chino into a tourist attraction.” In Kwan’s documentary, he walks through the barrio chino and observes how it has been conjured up by the imagination or – to borrow Said’s term – how it has been “orientalized.” Kwan narrates: “Everything is artifice and pretense. Restaurants are decorated with glowing red lanterns and plastic golden dragons. Outside, costumed waiters in pigtails and coolie hats join hostesses in Chinese dresses and kung fu outfits to lure international tourists with American dollars” (see figure 3).

Fig. 3. Hostesses in Havana’s Barrio Chino.

The government of Cuba upholds this Chinese fantasy by making “use of its people with Chinese ancestry.” The government grants permits to descendants of the Chinese to open small businesses in the barrio chino. Therefore, those Chinese born in Cuba, that is, those costumed waiters in pigtails and those hostesses in Chinese dresses are called to act out their roles as Cuban citizens. Assistant professor of performance studies, May Joseph, declares: “citizenship is not organic.” Citizenship is not inherent or innate. Citizenship for Chinese born in Cuba is acquired in public and psychic participation in “Orientalism” as they masquerade in order to survive. Joseph says about the acquisition of citizenship: “close scrutiny of the ways in which citizenship is actually embodied…discloses a scenario filled with the anxious enactments of citizens as actors.” Indeed, close scrutiny of the masked Cuban Chinese is required, for as Kwan observes, “nothing is what it appears to be in Cuba.”

Kwan finds various actors in the barrio chino. At the government-run Bar Pekin, Kwan comes across Maritza Cok and Abel Lam, who he describes as “two Chinese Cubans cast in the roles of bartender and cook” (see figures 4 and 5). “They are perfect for the part,” says Kwan. Abel talks with Kwan and shares that when the bar and restaurant, at which he works, was opened, “one of the main requirements was that everyone must be a Chinese descendant.”

Fig. 4. Maritza Cok, a Cuban Chinese descendant, works as a bartender in Havana’s Chinese Fantasy.

Fig. 5. Abel Lam, a Cuban Chinese descendant, works as a cook in Havana’s Chinese Fantasy.

At the Martial Arts Square in barrio chino, Kwan meets Roberto Lee, a third generation Chinese (see figure 6). Lee’s only Chinese heritage is his maternal grandmother. This Chinese connection, notes Kwan, “was good enough for the Cuban government” to select Lee to go to China to study martial arts. Now, narrates Kwan, Roberto Lee is a “big star” in the Chinese fantasy of the barrio chino. Lee runs a martial arts practice there. He has taken up his public role and has stepped into the psychic position of a Cuban-born Chinese. Lee tells Kwan’s camera: “Even though I’m Cuban, sometimes I feel Chinese in training, seriousness and perseverance.” ?

Fig. 6. Roberto Lee runs a martial arts practice in Havana’s Chinese Fantasy.

Fig. 7. Ching Yi Ming enacts his Chineseness for customers in Havana’s Chinese Fantasy.

At Café Paris, Kwan takes his viewers to see Ching Yi Ming who acts the part of a “Cuban Chinese tropical fortuneteller.” Ming also performs Tai Chi for the café’s patrons (see figure 7). Ming, too, is a Cuban-born Chinese who must use what Kwan calls “his ‘Chineseness’ to ply his trade.” Kwan observes that Ming’s “kind of Chineseness appears everywhere in [that] free floating fantasy world.” This kind of Chineseness is a strategic spectacle that has its roots in “plantation cultures developed by enforced labor to supply…foodstuffs [like] sugar.” According to Milla Cozart Riggio in her work Play Mas – Play Me, Play We, identity and disguise often merged in the plantation culture where oppressed peoples looked toward the European colonizer with masked faces that hid their personalities. She states: “masking yourself and playing the ‘other’ that one is expected to be [became] a daily survival mechanism.”

Those like Maritza, Abel, Roberto and Ming are summoned as citizens of Cuba to masquerade or play mas as the orientalized “other” in the barrio chino. “This is how ordinary Cubans survive,” says Kwan. This masking of the self is part of life in Cuba where as Kwan tells us “a box of Cohibas – Castro’s favorite cigars – sells for a hundred and fifty American dollars on the black market [which] is more money than a Cuban doctor makes in six months.” Disguise is commonplace in an island where Kwan declares: “clandestine capitalism [flourishes] beneath the façade of state socialism.”

Trinidad

While the Chinese born in Cuba don costumes of embroidered silk cheongsams, mandarin tunics and cloth shoes, the Chinese born in Trinidad adorn themselves with sequins, glitter, feathers and beads as they play out various roles and participate in the Trinidad Carnival – an event that “dominates the national consciousness.” “Far from being an eruption of ‘the people,’” writes Richard Schechner, a professor of performance studies, “[the Trinidad Carnival] is the signature happening of an entire nation, the most prominent mark of [the island’s] culture.” Anna Soong, a first generation Trinidad-born Chinese, invites director Cheuk Kwan to come to the island to experience Carnival – that is, the nation’s signifier – and to visit her father’s restaurant called Soong’s Great Wall in south Trinidad.

Kwan meets Maurice Soong, a Hakka who migrated from China to Trinidad in 1948 to join a man he had never met. Maurice made the journey to be united with his father who had been working in the island since the 1930’s. In Trinidad, Maurice grew up in a village where he learned English and also helped his father in a general store. For some migrant families, “wives remained in China to maintain the ancestral home.” Kwan learns of the depth of Maurice Soong’s anguish over the separation from his mother who remained in China for several years before joining the family in Trinidad. In 1968, Maurice Soong opened Soong’s Snackette, a business that sold barbeque chicken and fries along with Chinese food. Later, in 1981, Maurice launched Soong’s Great Wall, a restaurant famous for having such customers as prime ministers and presidents. Soong’s chefs are still hired from China and the restaurant’s serving of barbeque-roasted pork and duck is one of the best Kwan has tasted. Yet, past what Maurice Soong describes as “the cleanest kitchen in Trinidad” and beyond the great wall, is the enactment of citizenship or the embodiment of a national condition through participation in the very public jumping, prancing and waving that are requisites of the Trinidad Carnival.

Kwan’s documentary episode does not open with shots of Soong’s Great Wall Restaurant.

Fig. 8. Anna Soong, a first generation Trinidadian Chinese, participates in the Trinidad Carnival.

Rather, Kwan’s opening sequence reveals that he has arrived in Trinidad in time to follow Anna Soong and her husband John Johnston – a fourth generation Trinidad-born Chinese – to the island’s capital for the Carnival street parade (see figure 8). Kwan sees Chinese faces in the throng of glittering people and is aware that these partakers in public revelry could be “the descendants of indentured laborers who came or the merchant class and general store owners who [arrived] later.” Kwan meets a Roman soldier dressed in gold and black. The soldier is Anna’s brother, Johnny, who is also playing mas.

Images of Carnival masqueraders – many Chinese masqueraders (see figure 9) – permeate Kwan’s investigation of the Chinese Diaspora in Trinidad as he repeatedly lays Maurice Soong’s story of migration and family in the Caribbean island, alongside moving pictures of costumed street revelers. Kwan creatively uses shots of sequined inheritors of the plantation, separation, tension, chaos, diversity, hybridity, resistance and survival as strong symbols of a nation. He laces these shots into interviews with Maurice, his wife Brenda and their children. In doing so, the Chinese experience becomes interwoven with a national narrative. Schechner writes:

Trinidad Carnival…combine[s] Africa, European and Asian celebratory techniques and practices to embody in the streets of Port of Spain and elsewhere on the island a range of community values: artistic creativity; release from the daily grind in an ecstasy of dancing, music-making, sex-play, drinking and other similar entertainments. Taken together these constitute both a nonconscious and a highly self-conscious celebration of Trinidad and Tobago as a…diverse nation emerging from colonialism.

Fig. 9. Chinese masqueraders participate in the Trinidad Carnival.

To abandon yourself and play mas as a native is to enter a national mental space and take to the public roadways – an action which stirs acknowledgement that you are a Trinidad citizen. For Johnny Soong, that “Roman soldier,” there is no doubt about his identity and allegiance. He affirms: “I am very patriotic towards my country Trinidad and yes, I’m Chinese, but I’m a Trinidadian Chinese.”

Conclusion

This paper illustrates that whether it is flashing a welcoming smile from the shade of a straw coolie hat or dancing in the sun-drenched streets of Port-of-Spain, citizenship is acquired through taking up a mental position and through public performance. While director and producer Cheuk Kwan uses the medium of the Chinese restaurant and the vehicle of food to explore the social realm; to expose the many ways of living Chinese, what he achieves with these island episodes is a revelation of the ways in which being Chinese imbricates being Caribbean. Personal stories of sacrifice and survival are embedded in and molded by a wider archipelagic struggle with identity and economic viability – making these Chinese descendants born in islands washed by the Caribbean sea; these Huayi; these “overseas Chinese” in Kwan’s documentary, Asian but totally Caribbean.

_________________________________________________________________

Marsha Pearce is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of the West Indies, St Augustine Campus, Trinidad and Tobago. This paper is dedicated to her grandfather who was born in Trinidad to a Chinese father and African mother. He worked as a chef in the 1950’s and 60’s, serving up meals in both Trinidad and Tobago.

Paper presented at the Asian Experience in the Caribbean and the Guyanas Conference at the University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida, November 1-3, 2007. Footnotes and bibliography have been deleted in this webpage. For original paper in its entirety, please contact [email protected].